„Why We Need Art Now“?, die Interviewreihe mit international schaffenden Medienkünstler*innen geht weiter: nachdem die ersten Künstlergespräche aufgrund von Covid19 leider räumlich getrennt stattfinden mussten, konnte ich Künstlerin Gabrielle Zimmermann nun in ihrem Wohnatelier über den Dächern von Stuttgart persönlich treffen. Dieser direkte Gedankenaustausch war eine besondere Freude. Hört euch die daraus hervorgegangene Audioaufnahme am besten gleich an und erfahrt so mehr über die spannenden Arbeiten der zwischen Frankreich und Deutschland pendelnden Künstlerin. Viel Spaß dabei.

Kategorie: Allgemein

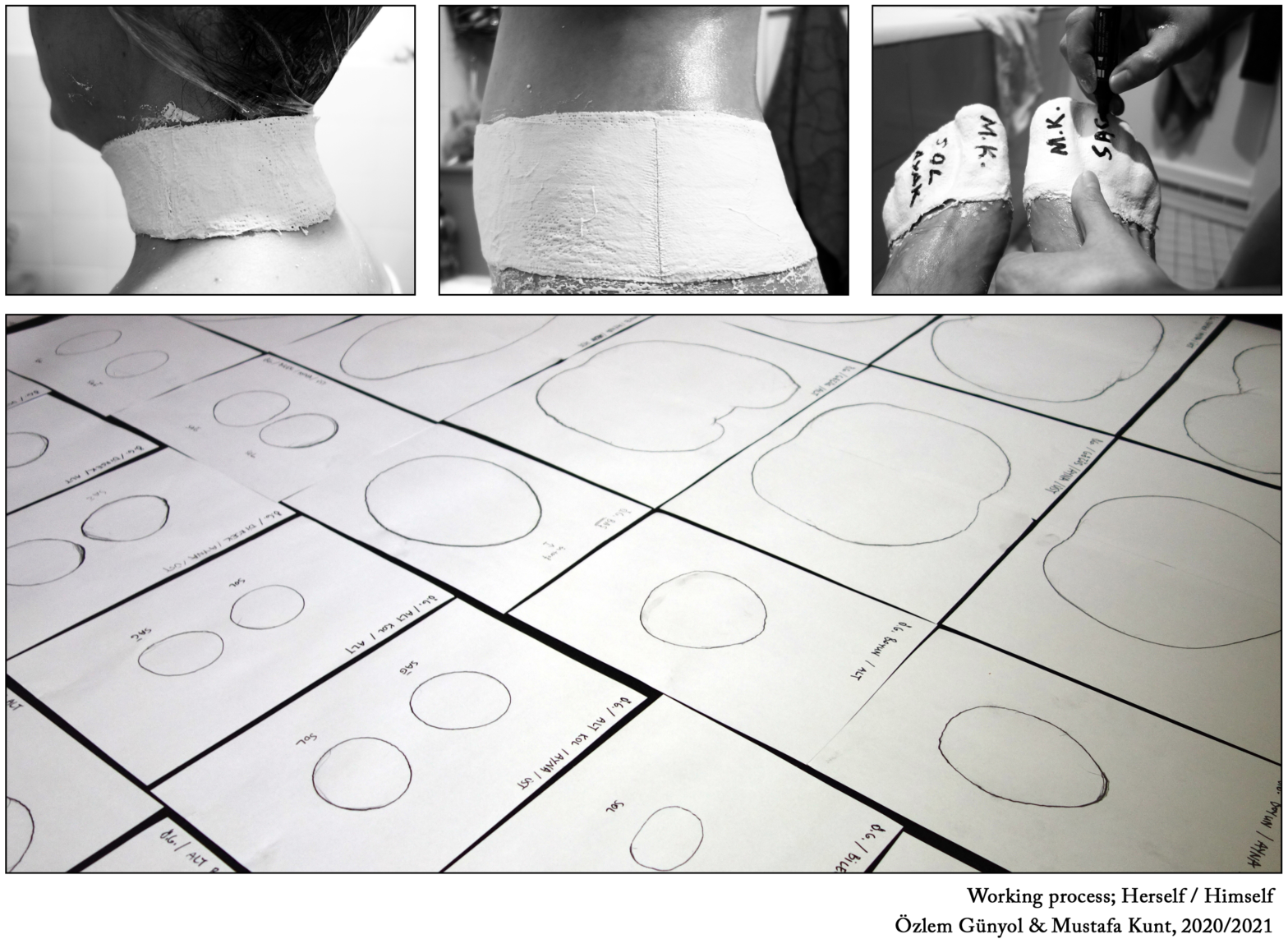

Özlem Günyol & Mustafa Kunt, “Herself / Himself”

The two Frankfurt artists Özlem Günyol and Mustafa Kunt talk in an interview about their latest work and how the pandemic has surprisingly changed their approach. We present the work here in advance. Hortense Pisano: Dear Özlem, dear Mustafa, what are you working on right now? Özlem Günyol, Mustafa Kunt: At the moment, we are… Özlem Günyol & Mustafa Kunt, “Herself / Himself” weiterlesen

Unter dem Pflaster ruht der Strand…

… in Brasiliens Küstenstadt Salvador de Bahia ist das tatsächlich so. Das komplette Gespräch mit dem brasilianischen Künstler, Jovan Mattos, über die erschwerten Realisierungsbedingungen von Street Art heute und über das Arbeiten mit dem typischen Pflasterraster, das die Straßen in Bahia prägt, findet ihr im Anschluss an diesen Video-Beitrag.

Jovan Mattos: “Pop-Kultur 2.0”

Während die Museen kurz vor der erneuten Schließung stehen, bleibt die Straße für alle offen. Die brasilianische Küstenstadt Salvador de Bahia verfügt über zahlreiche Graffitikünstler. Ihre Zeichen, Codes, Texte und Bilder sprühen diese urbane Aktivisten auf die teils leerstehenden Holzhäuser der historischen Altstadt als auch auf die moderne Betonarchitektur der autoreiche Neustadt. Jovan Mattos, Jahrgang’… Jovan Mattos: “Pop-Kultur 2.0” weiterlesen

Paola Anziché: Pure Materialpoesie

Dear Paola, I appreciate your work very much and would like to show them, as you know, in an exhibition. Now I have the opportunity to use this virtual studio visit to draw attention to the special nature of your sculptural objects, which we would now like to talk about in more detail. For all… Paola Anziché: Pure Materialpoesie weiterlesen

“Queerantine” by Jetmir Idrizi

“The camera serves as a gateway to a parallel dimension, where queer identities, through the language and power of their bodies, put binary and heteronormative systems to question, the systems that have tried to alienate and suppress them for many years.” Interview with Jetmir Idrizi, Berlin Lieber Jetmir, selbstbewusste, sexy Persönlichkeiten entdecken wir auf den… “Queerantine” by Jetmir Idrizi weiterlesen

Why We Need Art Now

Contributions and conversations with actors from art, design, dance and music Already at the beginning of the pandemic, I had the idea of creating a place in the worldwide web, that would counteract the current emptiness and silence of thought. Since the closure of all the exhibition houses, we have been lacking exchange and the tried… Why We Need Art Now weiterlesen